Louis Prang 1824 -1909

Believe it or not, the celebration of Christmas was once banned in Boston. It seems the Puritans considered it an invention of the devil. Although the law banning Christmas was repealed in 1681, it was not proclaimed a legal holiday here until 1856. This was the same year that Louis Prang, a German immigrant from Breslau Germany, came to America. He later became known as the father of the American Christmas card.

PRANG, Louis (1824-1909) was born in Breslau of a French

Huguenot father and German mother, and learned to dye print calico in his father's shop. After traveling as a journeyman in

Europe, he went to the United States in 1850, a refugee of the revolutionary period. He came well trained as a lithographer and

settled in Boston, where he started as a wood-engraver. He also became a lithographer, color-printer and publisher. Soon after

the Civil War he began printing chromo lithographs; and during the 1870's he began to issue color reproductions of famous

paintings.

PRANG, Louis (1824-1909) was born in Breslau of a French

Huguenot father and German mother, and learned to dye print calico in his father's shop. After traveling as a journeyman in

Europe, he went to the United States in 1850, a refugee of the revolutionary period. He came well trained as a lithographer and

settled in Boston, where he started as a wood-engraver. He also became a lithographer, color-printer and publisher. Soon after

the Civil War he began printing chromo lithographs; and during the 1870's he began to issue color reproductions of famous

paintings.

He was a writer on many subjects. He wrote the "Prang Method of Art

Instruction" and the "Prang Standards of Color." He is remembered for "Prang's Natural History

Series," published in 1873, and "Prang's Aids for Objective Teaching," which appeared in 1877, and both had a marked effect on the teaching of art throughout the United States. In 1882, the

pioneer of American lithographing organized the Prang Educational Company to publish drawing

books for schools, and Prang's water colors remained standard classroom equipment for many

years. Sylvester Koehler, the son of a Leipzig artist, who was brought to the United States as a

twelve-year old boy in 1849, became technical manager of Prang and Company in 1868,

one of the founders of the American Art Review, and curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

He was involved in politics. In 1860, the Massachusetts legislature, under the influence of the

Knownothings, proposed, and finally passed, the "two year amendment," depriving naturalized citizens of the right to

vote or hold office until two years after the completion of their citizenship. Many Republican legislators supported

this discrimination against the foreign-born. The Germans deeply resented such a challenge to their

dignity as adopted citizens of the United States. The Boston Germans met in Turner Hall, led by Charles

Heinzen, Prang and Adolf Douai, who urged their listeners to support only that party which

"does not measure civil rights by place of birth, or human rights by color of skin."

He is acknowledged as the creator of the Christmas card. Although such cards were prepared for sale probably as early as

the 1840's, it was not until about 1862 that the custom of sending them to friends and relatives became common. He

promoted the greeting card movement in America in 1856 and produced cards at his lithograph

shop in Boston every year after that date. He can thus be blamed for the fact that each

Christmas we have the tedious job of writing hundreds of Christmas greetings to our relatives and

friends.

Bibliography: Faust, Albert Bernhardt. The German Element in the United States II. Cambridge: Houghton Mufflin Co,

1909. Wandel, Joseph. The German Dimension of American History. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1979.

America through the eyes of German Immigrant Painters. Boston: Goethe Institute Boston, 1976.

Wittke, Carl. Refugees of Revolution. The German Forty-Eighters in America . Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1952.

SPRINGFIELD JOURNAL, MASS. - (An article about the history of greeting cards and Louis Prang, the Father of Christmas Cards).

"With all kind thoughts and good wishes for a happy

Christmas,

I give you greeting once again

On this most welcome morn

May it surpass in joyous reign

The best since you were born.

Gladness attend and fill your heart,

And every shade of care depart!"

Such was the tone of most 19th century and early 20th century Christmas greetings printed on the holiday card. The

sentiment was just as important as the colorful designs, with people treasuring their greeting cards enough to save and

collect them through the decades.

To the modern generation of youngsters accustomed to sending quick Messages via e-mail, the Christmas card

custom seems ancient and rooted deep in history. But it is not. Actually one of the newer Yuletide traditions, card

sending dates back only to the mid 19th century, and in fact was not embraced in the United States until 1875.

As the late 20th century gave way to the 21st century, Christmas card sending started to get mixed reviews. Once

thought to be the nicest and most personal holiday task, the signing and addressing of large numbers of cards became

a dreaded chore. With many people too busy to bother with pen and ink, the pre-printed name of the sender became a

welcome offer available at many stores. But there was still the need for writing out the envelopes. This was resolved

with pre-printed labels, especially if one had a fairly stable card list of friends, relatives, business acquaintances and

neighbors.

The desire to update everyone about news of births, deaths, marriage,

illness, job changes, academic achievement, vacations and even pets and the new living room curtains

was once conveyed via letters and notes inserted into the card. It was one way to "keep in touch," at

least once a year. But it took lots and lots of time and numb thumbs. "Necessity is the mother of

invention," and the long-winded Annual Holiday Letter was born.

Frequently the target of jokes and sarcastic comments, the highly detailed Annual Holiday letters hearken back to the

early 1800s and in fact are the seed that spawned the Christmas card as we have come to know it. Thus the adage

"What goes around, comes around" is also pertinent.

People, of course, have always exchanged verbal greetings that expressed wishes for a happy Yuletide. This was easily

done when everyone lived in close-knit communities and had no need to put their greetings in writing. As the practice

of sending children away to boarding school became more and more common, the custom of assigning the children an

annual "Christmas piece" in their finest penmanship was born. At first using fine paper to enumerate their scholastic

and social achievements, the schoolchildren were eventually provided with holiday paper for the purpose. Adorned with

borders, religious scenes, motifs from nature and scrolls, these sheets were hand-tinted, often by the young writers

who never failed to extend the heartiest Christmas wishes to parents and other dear relatives.

It should be noted that such customs were not a part of New England's history, for the observance of Christmas failed to

take root here until the last half of the 19th century with the arrival of European immigrants with non-Puritan ancestry.

Postage was costly both in the United

States and in England. Rates were determined by the distance between the sender's location

and the receiver's address. Calculated by miles, it was once assumed that the receiver would also

pay the postage upon receipt. With such a burden, most people discouraged mailings of any type unless the reason

was very important.

That changed in 1840 with postal reform in England and the introduction of the Penny Post, which introduced uniform

rates to any location, no matter the distance and also placed the burden of cost upon the sender. The notion spread to

other countries, including the United States, and other factors played a role as well. By 1840 railroads were

present to provide quick delivery to great distances. No longer was the mail in the hands of the postal rider on

horseback or even in the horse drawn mail cart. The rails moved carloads of mail from one depot to another in a flash

and opened new possibilities for Christmas card sending.

Not only was the Annual Christmas Piece now affordable for youngsters to send, but adults also were better able to afford

the lower rates to wish a far-away friend or relation a happy Yuletide.

Sir Henry Cole was one of the first to recognize merit in sending a printed card to many friends, relations and

acquaintances. He made a suggestion for its design to artist John Calcott Horsley in 1843 and 1,000 copies of the card

sold at one shilling each. The greeting "A merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You" was an integral part of the

design that featured three panels. At the left was a reminder of a need to feed the hungry and at the right a sketch of the

clothing of the naked. These acts of charity balanced the center panel that showed three generations of one family

toasting the season. Despite complaints from Temperance devotees that the theme endorsed drinking of alcoholic

beverages, the card was a success and gave birth to a whole new industry as well as a time-honored tradition that

soon spread across the Atlantic to the United States.

Before long, new companies began printing holiday cards and established stationers stocked a supply in time for

Christmas sending. Marcus Ward, the Castell Brothers, Dickes & Mansell,

Thomas De La Rue and others are now

highly regarded for their contributions to the growth of the Christmas card industry. These cards found their way to the

United States, both as imports and as welcome "remembrances" in the mailbox. By 1850, the New York

lithograph firm of R. H. Pease came out with a Christmas card that might well be the first printed in the United States. It

was described by George Buday. "The design includes the features of a small, rather elf-like Santa Claus with fur

trimmed cap, sleigh and reindeer. A ballroom with dancers, the building marked 'Temple of Fancy,' an array of

Christmas presents and Christmas dishes and drinks decorate the four corners of the card, while in the center, we

see a young couple with three children visibly delighted with their presents; behind the family group a black servant is

laying the table for the Christmas dinner. In addition to the central 'A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year' the

ornamented lettering includes 'To:' and 'From:' with spaces to be filled by the sender." Only one example exists today,

and is in the archives of the RustCraft Company.

The real "Father of the American Christmas Card" is Louis Prang, a German immigrant who came to America in 1850.

Like other newcomers to the New World, Prang was full of hope, ideals, optimism and a burning desire to make his

mark in life. He made the Roxbury section of Boston his home and was first employed as an engraver with Gleason's

as well as with Joseph Mayer. By 1860 Louis Prang set up his own business that utilized a method of color printing with

a series of metal plates rather than lithographic stone. The result was a richly hued image that far surpassed the hand

tinted black and white engravings and lithographs produced by companies like Currier & Ives or Kellogg. Better yet, what

worked for ordinary printed products would also work for the Christmas card.

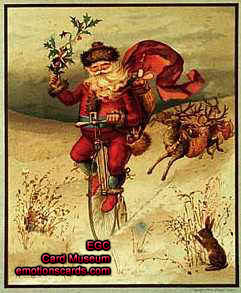

Made in Massachusetts, the first modern, color printed Christmas card was produced in 1875. The quality of print

was sheer perfection, and the designs were exquisite portrayals of flora and fauna, children, angels, fruit and other

symbols of the season. The cards were an immediate hit with the public, which demanded more.

A man of high standards, Louis Prang decided to hold annual contests with substantial cash prizes for new

artistic designs to be used for his cards. With as much as $100 or even $300 (a whopping sum in the 1870s and 1880s)

awarded for the winning entries, fabulous artists like Elihu Vedder, Will H. Low and Thomas Moran eagerly created

and submitted their designs to Prang. These are in great demand by today's collectors, for the reverse side of the

card notes that it is a prize-winning entry and states the artist's name.

Needless to say, Louis Prang's business created much

excitement in the art world and helped elevate the custom of card sending to an art. With tastes leaning to the opulent

during the Victorian age, even in New England, Prang's cards included silken fringe, silken cord, tassels and other

richly sensuous touches. They were expensive to buy, but Prang never forgot that the market included those with slim

wallets. There were also lovely cards on an affordable level, identified at the bottom as a product of the L. Prang

Company and the date.

By 1890 the market was flooded with cheap imitations of the fine products created by Prang,

Raphael Tuck, Marcus

Ward and the initial group of European and American card makers. Imports from Germany caught the imagination of the

public since they included mechanical components that folded, jumped up or out and often swayed from left to right

with aid of a paper tab. Where Prang had used rich layers of mellowed gold ink, the cheap imitators applied glue and

sprinkled sparkling glitter or other crushed material that looked like snow. The new cards were embossed and

included cutout areas. But the verse lost its significance, and some cards hardly offered a greeting to the receiver. They

became a novelty that got more and more elaborate.

Louis Prang decided that he would not compete in this market. He refused to lower his standards and ceased

production of Christmas cards soon after 1890. He did not abandon artistic printing, however, but continued good

quality work after merging with a company named Taber and the Taber-Prang operation relocated to Springfield in 1892.

The postcard made its appearance at the end of the 19th century, thanks to a decision by the U. S. Postal Service and

a contract awarded to Springfield's Elisha Morgan. By the late 1890s and early 1900s, the brilliantly colored penny

postcard had all but eclipsed the old fashioned Christmas card that came with its own envelope. Some of these cards

were printed in the United States, with a large number also imported from either England or Germany. The cards were

pretty, cheap to send and less trouble to address. There was room for a brief greeting that could be tailored to each

person. One shortcoming was a lack of privacy, since the greeting was available for anyone's eye to read.

By the 1920s the traditional Christmas card was back again, in much simpler form, but with its own envelope. Sealed

envelopes cost a penny more to send, while unsealed items could be sent second class for less money. This mattered,

for people were now sending dozens and sometime hundreds of cards.

The 1960s ushered in the sarcastic "studio" card, with its stark design and pointed greeting. By the 1970s and since

the public has rediscovered its preference for more artistic cards that often include rather long and poetic greetings.

With the conclusion of this article it is fitting to hail the 125th

anniversary of the first Christmas card printed by Louis Prang in our own Massachusetts. It is also fitting to borrow a

few lines of verse from a lovely old card and extend a greeting to SPRINGFIELD JOURNAL readers.

"Welcome to joyous Christmas time!

So ring the bells with merry chime

And children's voices gaily call,

A Happy Christmas to us all."

- Springfield Journal

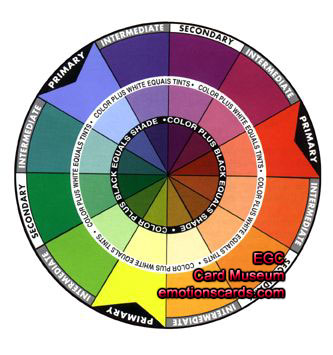

Louis

Prang developed a color wheel to show primary, secondary, and intermediate

colors with their shades (colors mixed with black) and tints (colors mixed with

white).

Louis

Prang developed a color wheel to show primary, secondary, and intermediate

colors with their shades (colors mixed with black) and tints (colors mixed with

white).

There are 12 colors in Prang’s color wheel.

Primary colors (red, yellow and

blue) are pure colors. Secondary colors (orange, green a nd

violet) can be made by mixing two primary colors together. Intermediate colors

are made by mixing primary and secondary colors together.

nd

violet) can be made by mixing two primary colors together. Intermediate colors

are made by mixing primary and secondary colors together.

PRANG, Louis (1824-1909) was born in Breslau of a French Huguenot father and German mother, and learned to dye print calico in his father's shop. After traveling as a journeyman in Europe, he went to the United States in 1850, a refugee of the revolutionary period. He came well trained as a lithographer and settled in Boston, where he started as a wood-engraver. He also became a lithographer, color-printer and publisher. Soon after the Civil War he began printing chromo lithographs; and during the 1870's he began to issue color reproductions of famous paintings.

He was a writer on many subjects. He wrote the "Prang Method of Art Instruction" and the "Prang Standards of Color." He is remembered for "Prang's Natural History Series," published in 1873, and "Prang's Aids for Objective Teaching," which appeared in 1877, and both had a marked effect on the teaching of art throughout the United States. In 1882, the pioneer of American lithographing organized the Prang Educational Company to publish drawing books for schools, and Prang's water colors remained standard classroom equipment for many years. Sylvester Koehler, the son of a Leipzig artist, who was brought to the United States as a twelve-year old boy in 1849, became technical manager of Prang and Company in 1868, one of the founders of the American Art Review, and curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

He

was involved in politics. In 1860, the Massachusetts legislature, under

the influence of the Knownothings, proposed, and finally passed, the "two

year amendment," depriving naturalized citizens of the right to vote or

hold office until two years after the completion of their citizenship.

Many Republican legislators supported this discrimination against the

foreign-born. The Germans deeply resented such a challenge to their

dignity as adopted citizens of the United States. The Boston Germans met

in Turner Hall, led by Charles Heinzen, Prang and Adolf Douai, who urged their

listeners to support only that party which "does not measure civil rights

by place of birth, or human rights by color of skin."

He

was involved in politics. In 1860, the Massachusetts legislature, under

the influence of the Knownothings, proposed, and finally passed, the "two

year amendment," depriving naturalized citizens of the right to vote or

hold office until two years after the completion of their citizenship.

Many Republican legislators supported this discrimination against the

foreign-born. The Germans deeply resented such a challenge to their

dignity as adopted citizens of the United States. The Boston Germans met

in Turner Hall, led by Charles Heinzen, Prang and Adolf Douai, who urged their

listeners to support only that party which "does not measure civil rights

by place of birth, or human rights by color of skin."

He is acknowledged as the creator of the Christmas card.

Although such cards were prepared for sale probably as early as the 1840's, it

was not until about 1862 that the custom of sending them to friends and

relatives became common. He promoted the greeting card movement in America

in 1856 and produced cards at his lithograph shop in Boston every year after

that date. He can thus be blamed for the fact that each Christmas we have

the tedious job of writing hundreds of Christmas greetings to our relatives and

friends.

Bibliography:

Faust,

Albert Bernhardt. The German Element in the United States II. Cambridge:

Houghton Mufflin Co, 1909.

Wandel, Joseph. The German Dimension of American History. Chicago:

Nelson-Hall, 1979.

America through the eyes of German Immigrant Painters. Boston: Goethe

Institute Boston, 1976.

Wittke, Carl. Refugees of Revolution. The German Forty-Eighters

in America . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1952.

Copyright © 1996-2000

Davitt Publications.

All rights reserved.

In

1975, the United State Postal Service issued a Postage Stamp commemorating an

early Christmas Card by Louis Prang. (Click on thumbnail image to view

entire sheet and a close-up of stamps).

In

1975, the United State Postal Service issued a Postage Stamp commemorating an

early Christmas Card by Louis Prang. (Click on thumbnail image to view

entire sheet and a close-up of stamps).

Visit our Greeting Card Galleries where we proudly exhibit over 1000 Vintage Cards where we proudly exhibit over 25 original Louis Prang cards. .

Emotions Greeting Cards©

/ VH Productions©, 1998-2003 All Rights Reserved

MAIN SITE ~ HOME